Climate Change is a Racial Justice Issue for Millions of Renters

Over the past few months and especially the past few weeks, we’ve seen an arguably unprecedented awakening to a profound truth. It is that while pressing problems like COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on Black people in the U.S. and racialized police brutality seem separate, they are in fact all symptoms of our social and economic system that operates on the devaluation of Black lives. Another well-known symptom of this system is that Black Americans have the lowest homeownership rate of any racial group.

Due to a long history of racist housing policies and other restrictions on personal freedom and wealth building, minority households are more likely to rent their homes than own them. Twenty percent of Black households are extremely low-income renters, compared to six percent of white non-Hispanic households.

Now, with a busy hurricane season quickly approaching, we must consider these facts in the context of a changing climate that is driving more frequent and more severe extreme weather events. As climate justice essayist Mary Annaïse Heglar writes, “Climate change takes any problem you already had, any threat you were already under, and multiplies it.”

Unfortunately, we see this threat multiplier playing out for renters in that low-income renters of color are hit first and worst when natural disasters strike. As evidenced by research from Groundwork USA and others, neighborhoods that could not attract investment due to racist housing policies starting in the 1930s are today the most vulnerable to flooding and heat waves. Unlike higher income homeowners, renters may not be able to stock up on food or relocate during a disaster. And despite renters’ higher vulnerability, federal recovery resources prioritize homeowners over renters.

The fact that low-income renters, who are disproportionately Black, are particularly vulnerable to climate change both during and after disasters is a racial justice issue. And it’s not a small one. Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies estimates that over 10 million renter households live in zip codes that incurred over $1 million in home and business losses between 2008–2018 due to natural disasters.

Making Housing Climate-Ready Takes Innovative Financing, Incentives, and Regulation

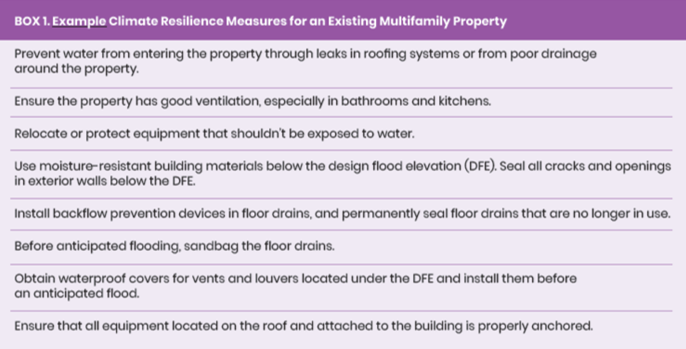

One way to reduce the near- and long-term impact of a disaster on low-income renters is to ensure that the rental properties they live in (affordable housing) can remain functional throughout the disaster and bounce back to normal operations quickly afterward. In other words, to ensure the properties are climate resilient. For example, for a building that is exposed to flood risk, a climate resilience measure would be to ensure water can’t enter the property through leaks in the roof or poor drainage around the property. The owner of that building may also want to elevate critical equipment, like HVAC equipment, from the ground floor so that it doesn’t get flooded and destroyed.

Box 1 provides additional examples of climate resilience measures. The specific measures that make sense for a property will depend on the hazards to which it is exposed. In addition to flooding, hazards include extreme heat, blizzards, high winds, and wildfires.

A working paper released today, Identifying, Valuing, and Financing Climate Resilience in Multifamily Affordable Housing, outlines progress that has been made on making affordable housing climate-ready and what needs to happen to upgrade properties at scale. The paper is authored by the Climate Resilience Finance Working Group of the Sustainability in Affordable Housing Lender Learning Network, which I coordinate and which is itself part of the Energy Efficiency for All initiative.

First among the challenges to making affordable housing more climate resilient is property owners’ and residents’ limited knowledge of why climate resilience is important and what projects mitigating climate risks look like. Fortunately, several resilience assessment tools can be used to assess what kinds of hazards a building is exposed to and identify opportunities to mitigate those hazards. Now, regulation and incentives need to make use of those tools mainstream.

A second challenge is that unlike energy and water efficiency that lower utility bills, resilience measures do not lead to clear cost savings. This makes it difficult to finance those measures using private sources of capital. Our working group recognizes that there are, however, savings to be had. According to our analysis, many resilience measures can lead to future savings from lower post-disaster recovery costs, lower insurance premiums, and lower tenant vacancy. We were focused primarily on how these savings accrue to a building owner rather than directly to tenants because it’s important that building owners can invest in resilience upgrades without raising rents to pay for them.

Unlocking private financing for resilience projects by recognizing and quantifying the future financial benefits of those upgrades is needed, but it is not sufficient. That’s because while building owners pay for the upgrades, other stakeholders — namely housing lenders, insurers, and the public — reap much of the benefits. These stakeholders that ultimately benefit from resilience investments must therefore contribute to the upfront payment of measures in the form of incentives provided to the building owner.

In addition to increased knowledge of and funding sources for resilience upgrades in affordable housing, we need ambitious building codes, certifications and rating systems, and information transparency. These foundations of resilient investment are necessary to drive building upgrades nationwide as quickly as possible.

Climate Investments Must Be Intentionally Anti-Displacement

Over the last few months, it’s become especially evident that the same improvements that make homes better able to withstand and recover from weather-related crises also makes them healthier and safer to live in when sheltering in place during a pandemic. By becoming more climate resilient, multifamily housing properties not only better serve residents, they become pillars in the overall system of community resilience infrastructure.

Still, we must proceed cautiously. Research commissioned by the Strong, Prosperous, and Resilient Communities Challenge shows that investments in climate adaptation and mitigation can unintentionally contribute to displacement of low-income households by raising property values and cost of living in the neighborhood.

Recognizing both the necessity and the potential risks of prioritizing lower-income renters of color in climate preparedness planning, plans to invest in climate resilient rental housing must be made as part of a broader community-led strategy. Those strategies must ensure that investments, including climate-related ones, strengthen the community rather than threaten it. Right now, more people in the U.S. than ever before are calling for the defunding of systems that perpetuate racism and a shift of those resources into Black communities. Low-income renters must be among the leaders in that collective visioning and action, and the resulting investments in housing must be made with a changing climate in mind. That way, we will all have homes where we can gather, shelter, plan, and recharge to transform the world in the years ahead.