By: Molly Bertolacini and Jalissa Williams

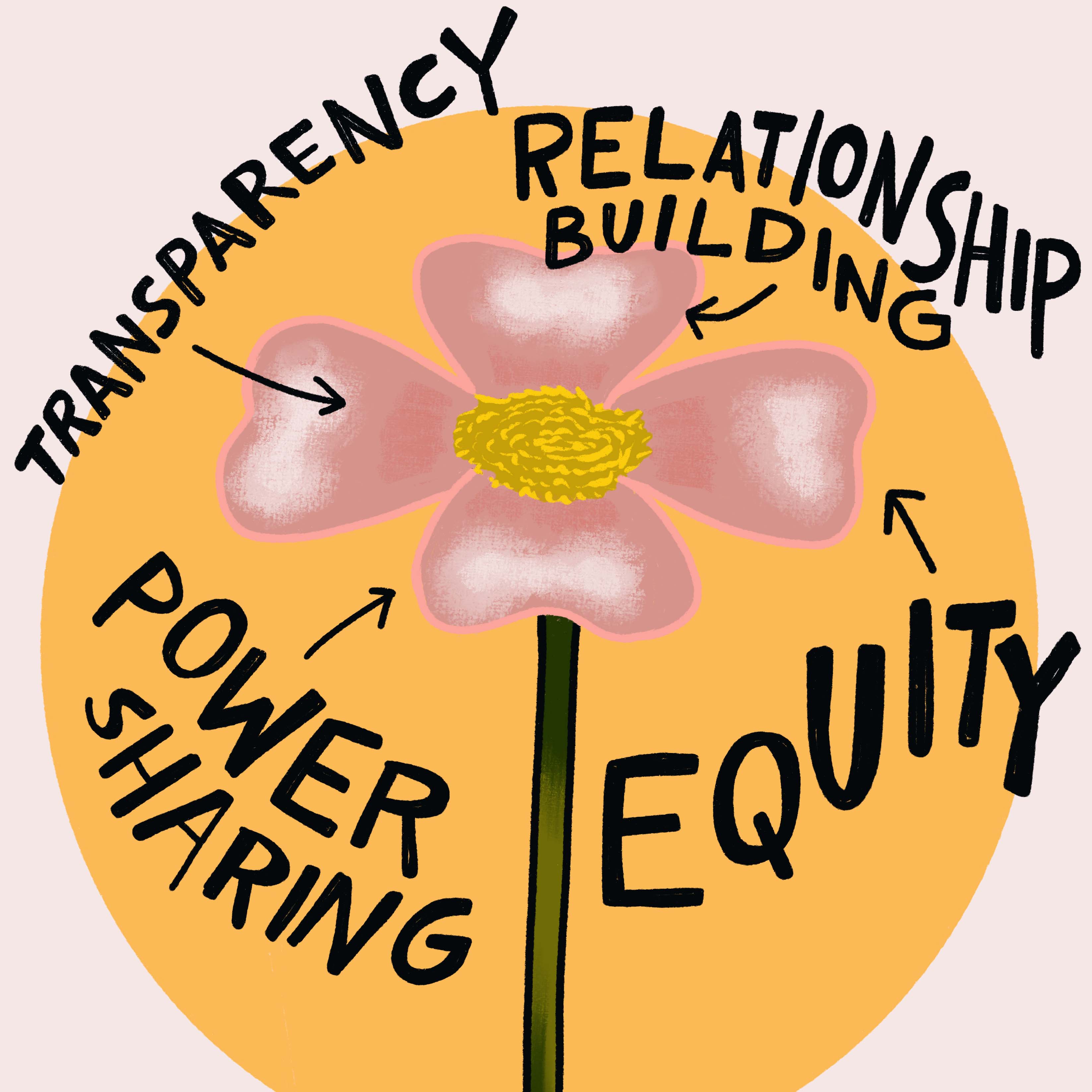

Storytelling in the environmental movement works to connect the experiences of people and groups, share a message, and humanize what is often technical climate or energy work. Storytelling can be done equitably when the relationship and partnerships are prioritized more than the content creation, when transparency and power-sharing among partners are uplifted throughout the process, and when equity is a central focus of the partnerships and the stories themselves.

Transforming stories into a means of connecting organizations and systems to each other has always been built into the fabric of the environmental movement, but historically Big Greens (well-funded, traditionally white-lead, environmental groups working at the national and international levels) have led campaign-based storytelling initiatives as a way to capitalize on work from community- and place-based organizations in order to raise awareness of the Big Green’s special interests or to draw attention to their campaigns.

A select group of staff within the Energy Efficiency For All (EEFA) initiative questioned if the existing methods within the field align with our project’s values of partnerships, transparency, power-sharing, and centering equity. After developing the principals, the group took an additional year to slow down the work and learn from a community-based organization who was operating in a way that aligned with those principals. Learnings from that relationship led to the development of guiding values that are intended to work alongside the principals discussed in part 1. These values have helped us to ensure that we are building deeper, lasting relationships between partner organizations, and doing so in a way that is not extractive, but rather uplifting.

Guiding Values:

- Relationship-centered work is a key facet of humanizing energy/housing work

- Transparency goes beyond notifying partners that work is happening.

- Engage in power sharing.

- Taking steps towards institutionally valuing both lived experience and non-technical expertise can move a project closer to an equitable process/outcome.

Image Credit: Jessica Russo

Image Credit: Jessica Russo

Relationship Building

To move toward authentic and transformative partnerships, and people-focused solutions, a greater emphasis must be placed on the development of the relationship itself. Relationship building takes time, trust, patience, honesty, co-creation, and more. Prioritizing the development of a relationship may mean stepping back from content creation, advocacy “wins,” monetary successes, report writing, or other deliverables. Rather than prioritizing tangible outcomes or products in a partnership, a successful and trusting relationship should be considered a win. By focusing on deepening our relationships with partners rather than content creation or transactional arrangements, we are already taking a step in the right direction to humanize climate, energy, and housing work, because we are putting people first throughout the process.

Transparency

In nonprofit organizations, especially in Big Greens, bureaucracy, sensitive campaign content, a deeply rooted sense of perfectionism, and antiquated administrative systems can lead to a lack of transparency, both within the organization and with external partners. When cultivating authentic relationships with community-based organizations, it is critical to go above and beyond what may be considered “standard” to create a transparent working environment and build trust. This requires a prospective outlining of engagement processes, highlighting potential barriers or complications, and fully outlining each partner’s objectives. Partners should not have to ask for this information, it should be proactively provided at the onset of the relationship/project. This includes, but is not limited to, delays in contract execution, timelines for payment plans, budgeting structures, necessary deliverables, communication guidelines, separate objectives that do not immediately and overtly involve all parties in the relationship, and more. It is also important to step back throughout the process (not just at the start) and make space for partners to evaluate the structures in place and determine that the work meets their needs, not just the needs of the staff at the organization with more privilege.

Power Sharing

Large environmental organizations with significant resources (e.g., staff time, funding, etc.) often drive forward advocacy efforts and public awareness campaigns, serving in a project management or leadership capacity. Smaller community-based groups or individuals with real life experience are often brought in along the way to provide stories that pull at the heartstrings of decision-makers and politicians. This method results in an inequitable distribution of power in terms of whose priorities are pushed forward in the environmental movement (Big Greens), and whose get left behind (community- and place-based organizations). To make meaningful change in climate science and advocacy, the priorities that are presented to decision-makers need to be those of the communities and organizations that are experiencing the adverse effects of climate change, pollution, energy burden, food insecurity, and more. To ensure that the needs and proposals of those most acutely affected by the climate crisis are centered in policy discussions, organizations that have more privilege (e.g., larger endowments and budgets, political reach, or staff capacity) should be in a constant state of self- and situation-examination. This is to ensure that the priorities and goals of organizations with less privilege are still able to set objectives to elevate and drive the projects forward. In this instance, it is the responsibility of the larger organization (i.e., NRDC) to provide or help to secure financial support or other resources that the partner may require to successfully move the work forward.

Equity

Two major issues exist within storytelling work regarding equity. One, a reliance on existing systems of power devalues the lived experience of impacted individuals and communities; and two, technical experience/expertise is perceived to have more value than non-technical experience/experience. Both issues stem from an unspoken rule within the field that academic-based skillsets are more legitimate due to their validation from established institutions (i.e., they are quantifiable: “Cheryl has a master’s degree and four years of experience working at a Big Green.”) What this takes away from the work is the richness that comes from a wide diversity of experiences by engaging artists and other creatives, as well as a lack of representation from the most impacted communities (communities that are hardest hit by climate issues frequently lack the privilege of having a strong representation within the institutions that provide these quantifiable credentials). There is more than one way to avoid these inequitable outcomes, but Big Greens can start working towards that by incorporating both technical and non-technical expertise into their requirements for job candidates and allowing applicants to use lived experience in place of academic or professional experience when they apply. Centering equity will require a slowdown of the process while you and your partners build, learn, and adopt your new system. Putting these practices into place is an essential first step to move towards an internal culture where doing work in an equitable manner comes as second nature and does not unnecessarily slow down processes or progress.